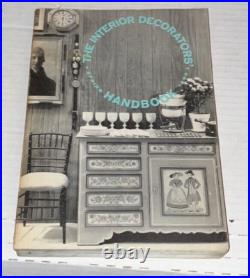

INTERIOR DECORATORS HANDBOOK 1960 Semi annual classified by products and services showing of suppliers with addresses Geographical listing branch showrooms and sales offices of advertisers index to advertisers Alphabetical register of in major trade cities Product finding index expressly for decorators and designers interior decorating staff of department and furniture stores Hall Publishing Company 230 Fifth Avenue New York 1 NY 484 pp 2.50 per year 2 issues to trade only. Mid-century modern (MCM) is a design movement in interior, product, graphic design, architecture, and urban development that was popular in the United States and Europe from roughly 1945 to 1969, [1][2] during the United States’s post-World War II period. The term was used descriptively as early as the mid-1950s and was defined as a design movement by Cara Greenberg in her 1984 book Mid-Century Modern: Furniture of the 1950s. It is now recognized by scholars and museums worldwide as a significant design movement. The MCM design aesthetic is modern in style and construction, aligned with the Modernist movement of the period. It is typically characterized by clean, simple lines and honest use of materials, and it generally does not include decorative embellishments. This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). Tract house in Tujunga, California, featuring open-beamed ceilings, c. Detail of Copan, a Niemeyer building in São Paulo, Oscar Niemeyer. The mid-century modern movement in the U. Was an American reflection of the International and Bauhaus movements, including the works of Gropius, Florence Knoll, Le Corbusier, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. [3] Although the American component was slightly more organic in form and less formal than the International Style, it is more firmly related to it than any other. Brazilian and Scandinavian architects were very influential at this time, with a style characterized by clean simplicity and integration with nature. Like many of Wright’s designs, Mid-century architecture was frequently employed in residential structures with the goal of bringing modernism into America’s post-war suburbs. This style emphasized creating structures with ample windows and open floor plans, with the intention of opening up interior spaces and bringing the outdoors in. Many Mid-century houses utilized then-groundbreaking post and beam architectural design that eliminated bulky support walls in favor of walls seemingly made of glass. Function was as important as form in Mid-century designs, with an emphasis placed on targeting the needs of the average American family. Eichler Homes – Foster Residence, Granada Hills. In Europe, the influence of Le Corbusier and the CIAM resulted in an architectural orthodoxy manifest across most parts of post-war Europe that was ultimately challenged by the radical agendas of the architectural wings of the avant-garde Situationist International, COBRA, as well as Archigram in London. A critical but sympathetic reappraisal of the internationalist oeuvre, inspired by Scandinavian Moderns such as Alvar Aalto, Sigurd Lewerentz and Arne Jacobsen, and the late work of Le Corbusier himself, was reinterpreted by groups such as Team X, including structuralist architects such as Aldo van Eyck, Ralph Erskine, Denys Lasdun, Jørn Utzon and the movement known in the United Kingdom as New Brutalism. Pioneering builder and real estate developer Joseph Eichler was instrumental in bringing Mid-century modern architecture (“Eichler Homes”) to subdivisions in the Los Angeles area and the San Francisco Bay region of California, and select housing developments on the east coast. George Fred Keck, his brother Willam Keck, Henry P. Glass, Mies van der Rohe, and Edward Humrich created Mid-century modern residences in the Chicago area. Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House is extremely difficult to heat or cool, while Keck and Keck were pioneers in the incorporation of passive solar features in their houses to compensate for their large glass windows. Mid-century modern in Palm Springs. Miller House, by Richard Neutra. The city of Palm Springs, California is noted for its many examples of Mid-century modern architecture. [4][5][6][7][8][9][10][excessive citations]. Architects include:[11][12]. Welton Becket: Bullock’s Palm Springs (with Wurdeman) (1947) (demolished, 1996[13]). John Porter Clark: Welwood Murray Library (1937); Clark Residence (1939) (on the El Minador golf course); Palm Springs Women’s Club (1939). Cody: Stanley Goldberg residence;[14] Del Marcos Motel (1947); L’Horizon Hotel, for Jack Wrather and Bonita Granville (1952); remodel of Thunderbird Country Club clubhouse c. 1953 (Rancho Mirage); Tamarisk Country Club (1953) (Rancho Mirage) (now remodeled); Huddle Springs restaurant (1957); St. Theresa Parish Church (1968); Palm Springs Library (1975). Craig Ellwood: Max Palevsky House (1970). Albert Frey: Palm Springs City Hall (with Clark and Chambers) (1952-57); Palm Springs Fire Station #1 (1955); Tramway Gas Station (1963); Movie Colony Hotel; Kocher-Samson Building (1934) with A. Lawrence Kocher; Raymond Loewy House (1946); Villa Hermosa Resort (1946); Frey House I (1953); Frey House II (1963); Carey-Pirozzi house (1956); Christian Scientist Church (1957); Alpha Beta Shopping Center (1960) (demolished). Victor Gruen: City National Bank (now Bank of America) (1959)[15] (designed as an homage to the Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, by Le Corbusier). Quincy Jones: Palm Springs Tennis Club with Paul R. Williams (1946); Town & Country Center with Paul R. Robinson House with Frederick E. Emmons (1957); Ambassador and Mrs. Annenberg House with Frederick E. Emmons (1963); Country Club Estates Condominiums (1965). William Krisel:[16] Ocotillo Lodge(1957); House of Tomorrow(1962). John Lautner: Desert Hot Springs Motel (1947); Arthur Elrod House (1968) (interiors used in filming James Bond’s Diamonds Are Forever); Hope Residence (1973). John Black Lee: Specialized in residential houses. Lee House 1 (1952), Lee House 2 (1956) for which he won the Award of Merit from the American Institute of Architects, Day House (1965), System House (1961), Rogers House (1957), Ravello (1960). Gene Leedy: The Sarasota School of Architecture, sometimes called Sarasota Modern, is a regional style of post-war architecture that emerged on Florida’s Central West Coast. Frederick Monhoff: Palm Springs Biltmore Resort (1948) (demolished, 2003[13]). Richard Neutra (Posthumous AIA Gold Medal honoree): Grace Lewis Miller house (1937) (includes her Mensendlieck posture therapy studio);[18] Kaufmann Desert House (1946);[19] Samuel and Luella Maslon House, Tamarisk Country Club, Rancho Mirage (1962) (demolished 2003)[13]. William Pereira: Robinson’s (1953). William Gray Purcell (with protégé Van Evera Bailey): Purcell House (1933) (cubist modern). Donald Wexler: Steel Developmental Houses, [20] Sunny View Drive (1961). Home developer, Alexander Homes, popularized this post-and-beam architectural style in the Coachella Valley. Alexander houses and similar homes feature low-pitched roofs, wide eaves, open-beamed ceilings, and floor-to-ceiling windows. Stewart Williams: Frank Sinatra House (1946) (with piano-shaped pool); Oasis commercial building with interiors by Paul R. Williams (1952); William and Marjorie Edris House (1954); Mari and Steward Williams House (1956); Santa Fe Federal Savings Building (1958); Coachella Valley Savings & Loan (now Washington Mutual) (1960); Palm Springs Desert Museum (1976). Paul Williams: Palm Springs Tennis Club (with Jones) (1946). Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. Walter Wurdeman: Bullock’s Palm Springs (with Welton Becket) (1947) (demolished 1996)[13]. Examples of 1950s Palm Springs motel architecture include Ballantines Movie Colony (1952) – one portion is the 1935 Albert Frey San Jacinto Hotel – the Coral Sands Inn (1952), and the Orbit Inn (1957). [21] Restoration projects have been undertaken to return many of these residences and businesses to their original condition. Scandinavian design was very influential at this time, with a style characterized by simplicity, democratic design and natural shapes. Glassware (Iittala – Finland), ceramics (Arabia – Finland), tableware (Georg Jensen – Denmark), lighting (Poul Henningsen – Denmark), and furniture (Danish modern) were some of the genres for the products created. In America, east of the Mississippi, the American-born Russel Wright, designing for Steubenville Pottery, and Hungarian-born Eva Zeisel designing for Red Wing Pottery and later Hall China created free-flowing ceramic designs that were much admired and heralded in the trend of smooth, flowing contours in dinnerware. The company was one of the numerous California pottery manufacturers that had their heyday in post-war US, and produced Mid-Century modern ceramic dish-ware. Edith Heath’s “Coupe” line remains in demand and has been in constant production since 1948, with only periodic changes to the texture and color of the glazes. [23] The Tamac Pottery company produced a line of mid-century modern biomorphic dinnerware and housewares between 1946 and 1972.